WINIFRED-EMMA: FORGET THE NOBLE TRUTHS CHAPTERS 6 – 10

November 29, 2008

___________________________________________

CHAPTER 6: JESSERENT

___________________________________________

THE SIXTH GATE

Jesserent, Jazzerant,, a splint armour, [O. Fr. jaseran (t), jazzeran – Sp. jacerina.]

The process of loosing the scriptures; the motives for Innana’s descent, jesserent, Molly’s bones; coverings; the cemetery re-visited; the dentists return; wave and mountain dream; Uccello’s St George and the dragon.

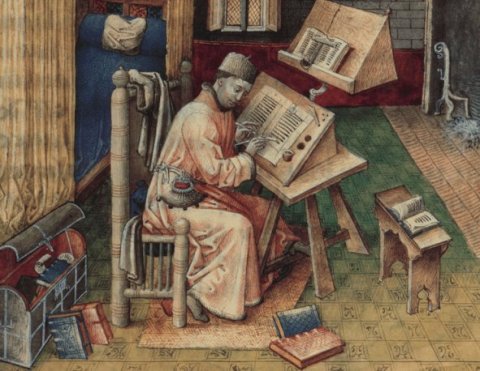

The process of loosing the scriptures

This process of loosing the scriptures, the rules or ‘laws’ by which she had lived her life was having an effect. w-e felt the ambiguity of the client in the hair-stylist’s chair, who says “I want a complete change” and then adds nervously “but don’t alter the length”.

The loosing by expansion, using additional information gleaned through the internet to change her relation to what she already knew by dilution had been a good plan, and had worked, was working. But the story of Inanna and her descent to the underworld had refocused the new material in a way she had not expected. It had re-connected her to things which she had already almost succeeded in forgetting, or at least ignoring. She had understood Death’s injunction, ‘to listen to the screaming’ to be, in theory, therapeutically, morally and socially a good thing, but to actually experience it was not pleasant. She realised now that to abandon the rules, meant also to a certain extent to abandon rationality, and though the rational had not ever been her god or goal, still the loss of it might tip her into the same pit into which her brother had fallen, and from which he had not been able to return. He had been stuck, in terms of the Inanna story, because unlike Erseshkegal he had had no comforters, and so, for him, the constant screaming had never stopped.

The motives for Innana’s descent, jesserent, Molly’s bones

So, thought w-e, the motives for Innana’s descent to comfort Ereshkegal were certainly mixed. Of course she would have wanted to stop her crying because Ereshkegal was her sister and was mourning the death of her husband, but also it would have been because the sound of crying was impinging on her life, and once she began to hear it, it would have increased in volume and become impossible to ignore.

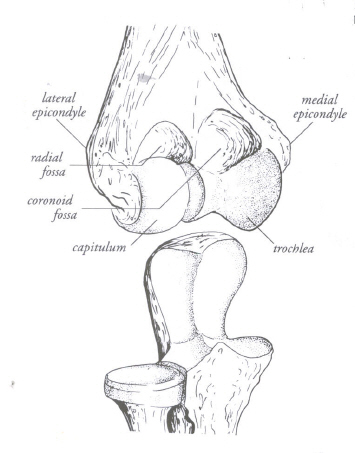

The computer had absolutely nothing to say on jesserent or jazzerant, and this in itself was unexpected, it brought w-e to a temporary halt, though apparently it had plenty to say about splints (548,000 hits) and armour (4,390,000 hits). The splints took w-e’s mind back to Molly’s broken arm, she knew Molly had been anxious about going to hospital to have surgery because the cardigan she had helped to drape around Molly’s shoulders had a beautiful Norwegian pattern, and when she admired it Molly said it had belonged to a friend of hers, who was in her nineties and had gone into hospital for something minor, but through a series of errors had been returned to the operating theatre four or five times, and died of an infection. Molly’s eyes, normally peaceful were wide open to something alarming, “I really don’t want to go in for surgery” she said, and later when w-e mentioned this, Sylvia said “I don’t blame her, I would not like to have to go in myself.”

“But don’t you think hospital hygiene will improve, after all there has been a lot of publicity about it? asked w-e.

“I don’t think so. When I was nursing as soon as a patient left a bed we would strip it, but we had a trolley by the bed, everything went into a trolley, now they pull bedclothes off and they go on the floor. Spreads infection. In Sweden they take the whole bed away to spray disinfect it, and a newly sterile bed is wheeled in for the next patient. We used to wash the whole bed frame with a special disinfectant, everywhere, including underneath and it was left to dry, for several hours, that way you could be sure it was safe. Now there is no time to do that, they use ‘wipes’, but only across the mattress, its not the same.” The dismissive way she inflected the word ‘wipes’ showed a strength of feeling unusual for Sylvia.

“So the patient gets into an infected bed.”

“Very often they do. We had basins for hand washing, one in every four-bed ward, with disinfecting soap in a bottle, sometimes I came home with my hands raw from washing, the doctors also used to wash hands between patients, now they don’t always.” She didn’t think things would change soon, “the whole system is against it, there is no sister to control the ward, make sure things are done rightly”.

w-e hoped devoutly not to have to enter hospital herself and she worried about Molly. When she met her next on their landing Molly was sitting with her hair in rollers, her head under a helmet hair drier of a kind w-e had not seen since the 1970s. The volunteer hairdresser had arrived, and was using the landing as her salon. w-e saw the mottled and blackened arm in a new kind of sling. Apparently the collar and cuff arrangement had been the wrong kind of support as the bone was splintered and separated from the head which had come out of the shoulder socket. This new kind of splint/sling was to help the head to connect back into the socket, but they thought it was unlikely to succeed, “They think there will have to be surgery.”

In order to encourage her and also because she did think it likely w-e said she thought god would be on Molly’s side, after all Molly spent her life in the service of god, spreading the word in an even peaceful manner, and knowing that she had the truth, must surely as Molly herself had said “make a difference”.

Coverings

As she sat on the tube on her first outing for weeks, w-e’s thoughts turned on armour as a covering, protective, healing, adorning, rank-signalling, she wrote a note as best she could bracing against the wobble of the train. Then she re-wrote it in capital letters in the hope of being able to decipher it later. Images of clothes and uniforms, of conformity and rebellion drifted unordered through her mind. She remembered talking with her friend Mark, who had gone to Ibiza, opened a club and disappeared into the money it made. He had opened her eyes to clothes, and through him she began to notice what they signalled, how much information they gave if you paid attention to them. For a while she had gone out to watch people on the street, each person coming towards her was so densely and richly defined, such shades and glimmerings of needs, neglects, compensations. She had become carelessly blind to them, forgotten the whole thing.

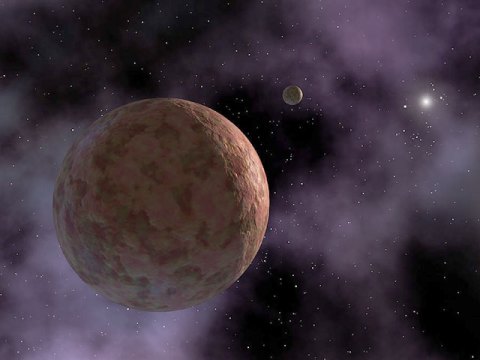

Now she connected coverings with rules, rules as protective, as splints, forbidding movement, necessarily restrictive, rules as obscuring, blocking the ears to alternatives, to the present, and these were necessary because all alternatives could not be gone through, not even once. Each enquiry would spread out creating new planets, suns, galaxies, the right answer, or indeed any answer could not be arrived at because enquiry was a creative force that constantly overtook each possible destination.

The disadvantage of imposed rules, the laws of religion or state, was their inflexibility, they were cumbersome and slow to modulate, whereas enquiry darted and flashed mercurially forward and backward, often inviting transgression. The desire to loose the rules she lived by, had been brought about because she recognised that her security had become her prison.

But there was to be no change of one order to another without moving through chaos, she understood this to be lawful, not the imposition of a law but the way it had to be, no new order could arise before the dissolution of the old, unless that is a person was living outside the constraints of time. It was time that folded and unfold events, like a pleated curtain drawn back and forth across a window, or perhaps it was memory which ordered things in sequence and out of sequence which seemed to hold and reinforce the old order, yet sometimes new thoughts came, from where? The story of Inanna, which she had been drawn to in the understanding that Ereshkegal represented some split off part of herself that was seeking reconciliation, now re-presented its narrative in terms of sibling relations. Her descent to comfort her own sibling had already been made, and to no satisfactory outcome, because in the end however much she loved her brother she could not agree to die with him, which is what he wanted.

The friend she met for lunch had an unusual approach to clothes. He told her that twenty years ago he had gone into a camping supply shop, for tent-pegs, or whatever, and it had a sale on, so he bought forty green t-shirts and was still wearing them. “Some are still new, or new-ish, if I have to go somewhere and look respectable I root through them for a new one.” His jackets, also green, were a series of identical easily recognisable garments, he was famous for having one permanently over the back of his office chair, giving out the message of his presence somewhere in the building, whilst in fact he might be, and often was, far away wearing another jacket.

He took off a green jacket revealing a green t-shirt, the fact that it was a much used one indicated that she was a friend for whom being respectable was not necessary, a complement in its way. His clothes spoke of a desire to halt or deny change, to appear consistently equable, and to be seen in his own terms, unvaryingly in his work role, this was comfortingly reliable, meant that he would be thought of as “always the same”, though of course this could not be true, his clothes were as deceptive as those of a Rolex wearing, chequebook clad man, though the motives for the deception might be different. Clothes showed how much power a person, desired, agreed to, or admitted to having, the power could be sexual, financial, political or it could be as ambitious as her friend’s clothes which showed an heroic denial or holding back of time.

Inanna’s powers were made visible by her crown, her lapis beads, her breastplate, her double strand of beads, her gold bracelets, her measuring rod and line, her royal robe. Life had formed round her, not just as a protective shell which is how w-e had always thought of armour, a place to hide, but as a declaration of her powers, magnificent like the armour w-e had seen in a museum, engraved and inset with gold and silver, embellished with cutting edges on elbow and knee, spiked helmets creating an aura of safety for the wearer who, close to, became lethal. Inanna’s powers defined her, separated her from others. When these outwards signs were removed, she was revealed in her nakedness she became one with her subjects, and her fate became the fate of all.

The cemetery re-visited

A few days later, w-e went out to post a letter and decided to carry on for a short walk, before it got dark, so she headed for the cemetery rather than up the steep hill to the duck pond, passing a couple of elderly women deep in conversation. The entrance to the cemetery was strewn all down the right hand side with plastic carrier bags of various sizes and colours, it looked as though a competition for plastic bag strewing had been held, and then she realized that the wind must have blown all the bags to that side, the left side had none, but then she wondered in the seventy five yards between the road, the big metal entrance gates and the entry to the cemetery itself, how had so many carrier bags been let go, most people visited in a car, as a notice on the fence warned ‘Stop Beware of Pedestrians’, ‘Be aware of pedestrians’ edited w-e crossly, noticing for the first time that a whole batch of instructions were also given about accompanied children and guide dogs.

Inside amongst the winter greys across the whole field of graves, there was a bright dotting of red plastic roses, and poinsettias of exactly the same red, the first ones she passed were on large double bed sized marble graves were clearly Christmas table decorations, poinsettias and fir cones, in baskets, with silvery bits, this looked like a surprisingly frugal recycling. Later on she saw some Christmas door wreaths, holly with berries and plastic red roses, or fir with cones, laurel and plastic lilac coloured anemones, in one case the string from which the wreath had hung on the front door trailed across the grave.

There had been several new Swiss chalet type rest homes for the watering cans built, one of these was now sited opposite the much visited, often chaotically disordered grave of the sixties singer, which had had a good clear out since she had last seen it. Beyond, where the new graves were she saw a young woman standing at the grave where she had seen oil lamps, “she must have come to refill the oil”, thought w-e, interested but not wanting to stare. As she rounded the curve of the path she saw the exceptionally small young woman changing her tiny Wellingtons for tiny shoes at the back of her four-wheel drive, so w-e felt she could now look over at the grave which seemed to hold even more flowers than before, huge lilies had arrived, but she didn’t like to make a complete inventory.

As she went on she saw the large teddy bear, which had been on the grave, now sitting on a new pine bench, provided for mourners under the trees, above it someone had hung a multicoloured woven banner, similar to a kind of new-agey priest’s stole she had once seen in church, and a set of metal wind chimes. The four-wheel drive took off with energy, probably not aware of anything much, let alone pedestrians. At the back of the teddy bear bench there was a cluster of vases, some were beautiful. What was going on? Was there a family feud, one side going down and putting the teddy bear and ‘our’ vases on the grave, the other side returning later to change things back?

Fascinated by the Christmas front-door wreaths, w-e counted twenty-five on the graves she passed, a few of these had little florists gift notes encased in plastic envelopes, and looked as though they had been delivered directly to the grave as a way of including the departed in the family celebrations.

At the main gates there was a group of eleven or twelve-year old boys, they radiated guilt, and actually huddled furtively, like a demonstration of a guilty huddle, she walked briskly past them, and on the way back passed elderly women still in the same spot, still earnestly talking. She also saw the man with the half-starved, ill looking dogs, he was a lot thinner himself, but no less threatening.

The dentists return

The days after new year passed and gradually dentists returned from their holidays, the flow of patients to and from the surgeries resumed. w-e had secured an appointment for the third day back of her own dentist, who had enjoyed a prolonged break in the American south, and took her abscess there. Lying back mostly with eyes shut behind a pair of plastic goggles she tried to relax but a mouth full of hands and implements, together with her fear of the processes made praying a better option, so she gave herself into god’s care continuously throughout the whole procedure. When she opened her eyes she saw hanging over her a round moon-like light, silvery with a hyacinth blue tint on the faceted glass at the rim. The next time she opened her eyes she seemed to be in a cavern looking up at distant alpine peaks, these were the mask and the white cuffs of the dentist and her assistant, another time she saw the soft gleam of her dentist’s eye as it peered into her mouth.

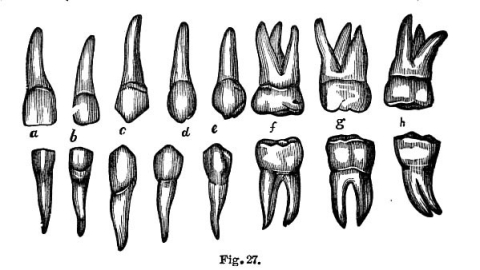

“We found the source of the infection” said her dentist, “ I expect you noticed the smell,” and indeed w-e had smelled the unpleasant puff of decay escaping her mouth. “The nerve was dead, it was black and rotting” added her dentist in an unusual spurt of vocalisation. “But I have cleaned it out and disinfected it”. w-e had to make a further appointment for the cleansing treatment to be repeated the following week, she was relieved to feel that she was no longer walking around as she had for the last month with pus from the rotting nerve inside her.

The next day she was alarmed to have another toothache, this time on the other side of her mouth, it was a Friday, and so rather than risk going on into the dentist-free zone of the week-end, she took herself back to the dentist, to see if she could have an emergency appointment. To her surprise the receptionist got up at once and said “I’m just going to find out if she will see you”, and came back saying that if w-e would wait the dentist would see her after the next patient. It was the afternoon and incredibly hot in the waiting room, the others waiting had shed their coats, and after a bit w-e also took off several layers, her coat, a jersey and a t-shirt.

She moved to sit some way from the receptionist who had a bad dose of the ‘flu’ saying apologetically that she did not want to re-infect herself. This proved to be a conversational opening for the woman opposite to give advice, about ’flu’, mothers and their children, in a transfixing flow of inaccurate medical information. Unless inhalations were carried out as she described, the poor receptionist would develop pneumonia, and then pleurisy followed inevitably by TB, but that would be alright because TB was now easily cured. w-e who knew that there were now strains of resistant TB and that cases of it were on the increase, managed to hold her tongue. “Mothers are the best doctors for their children” said the woman, “they know them, see them every day”. “She continued at length to recount the curing of her own son, brought back to her from New York because of his ’flu’, she discoursed on phlegm and as she did so gave a balletic mime of the site of the phlegm indicated by a hand touching her chest, using a rising gesture that showed its loosening and journey up to the throat, and a graceful turning of the hand conveyed its expulsion from the mouth. w-e wondered if her own flows of advice were as inaccurate and irritating, probably they were.

Through a window in the waiting room the sky looked a worrying colour until she identified it as the pink in a sky she had seen in a Monet painting, there was a fish-net of lichened green branches scratched glowingly across it, while through the other window the sky was a clear birds egg blue. Two transparent epoxy resin dolphins arched expensively from a blue curling wave on the receptionist’s desk, quiet fell on the waiting room, w-e waited.

Wave and mountain dream

Three nights later w-e dreamed she was on the side of a mountain with a female friend, looking down she saw the sea begin to splutter and boil, in her dream memory she knew of the danger of the giant wave, she told her friend they must leave, but they decided against the road they had come on, it was too low down, and they began to climb up the mountain where they would be safe. A third woman appeared who had chocolate that she offered them, w-e could not eat it, because it had nuts which she was allergic to, she worried that they would not find food. But at the top of the mountain they found a house, with a kitchen well stocked with food and decided to eat and leave money which w-e found in her pocket to pay for it.

Uccello’s St George and the Dragon

Years before w-e had tutored an exceptionally inventive seven year old American girl, who wanted to tell stories in her drawings. Her mother wanted her to make representational drawings of leaves and fruit. So they compromised, did a bit of each and in between w-e showed Cora-Belle postcards of the paintings and they talked about them. w-e remembered the Ucello painting now, because the boy hero St George was in armour and so she had just realized was the dragon, which had its own natural armour, only the chinless damsel was unprotected. The strangeness of this small painting lay for w-e in the fact that the damsel was passively holding a thread or lead which attached her to the dragon, she wasn’t tied to the dragon and could easily have separated herself from it if she had dropped the thread. She showed this to Cora-Belle, who bent over the card, her blond hair shocked forward, she looked up at w-e her eyes glazed, reaching back towards some source of knowledge, then she said in a dreamy voice, “I think they are the same person”, “the dragon and the damsel?” asked w-e, “yes” said Cora-Belle, “I think so.”

______________________________________

CHAPTER 7: LANGUAGE

______________________________________

THE SEVENTH GATE – LANGUAGE

the most diluting word so far; naked; the sound of cotton; memorial; checking out at the supermarket; jealousy; Donne’s poem; Helmshore refurbishment; rotting; Terminator Two; the flies; life stories; love and the most noble truth; Lent; first time reinstatement

language human speech: a variety of speech or body of words and idioms, especially that of a nation: mode of expression: diction: any manner of expressing thought or feeling: an artificial system of signs and symbols, with rules for forming intelligible communications, for use in e.g. a computer: a national branch of one of the religious or military Orders, e.g. Hospitilars.

The most diluting word so far

With this word the dictionary had come up with the most diluting word so far, whereas there had been no computer entries at all for jesserent, there were 197,000,000 for language. w-e entered additional qualifying words and found the following table of entries:

Language and

Number of hits

1.

Home

31,700,000

2.

Children

28,900,000

3.

Money

28,100,000

4.

Health

27,700,000

5.

Life

27,700,000

6.

Travel

21,800,000

7.

Food

18,600,000

8.

Religion

17,900,000

9.

Love

16,900,000

Language and politics, and death, and hope, and sport, and sex came next and in that order, language and babies hardly registered. w-e wondered if these numbers would be the same, if she were looking at the hits in Italian or Chinese, surely there would be cultural differences that would affect the order?

The languages she decided to look at, as most relevant to her purpose, were the ones connected to Inanna and Ereshkegal as Inanna passed through the seventh gate completely naked, Ereshkegal’s jealousy of Inanna, her killing rage and eye of death that left Inanna a corpse a piece of rotting meat to be hung on a hook in the wall. The insurance policy Inanna took out before she began her journey, the helpers created by her grandfather, their thereputic consolation of Ereshkegal, their negotiating and bargaining powers.

Naked

The computer connected naked with porn: films, and opportunities to meet ‘super hot girls ready to party’, or ‘free introductions to housewives, for a trial period.’ The front pages were all orientated towards supplying men with presumably naked at some stage, women, no invitations or trial periods for women to meet men, or other gender combinations. Probably they were represented somewhere in the forty-four million references to naked that Google had provided, but this was not the nakedness of Inanna, which in language terms was connected to vulnerability, powerlessness, a language unclothed in deceiving flattering disguises. A naked language, thought w-e, would be primal conveying meaning without room for doubt or misinterpretations, more a language of presence, of the swift transmission that tells you in the instant you meet someone for the first time an encyclopaedia of information, of attractions, and warnings, to be remembered later after events have run their course.

A Canadian woman told w-e of coming to London and staying by herself in an opulent apartment lent to her by friends of her parents. On her first evening she took herself out and succeeded in meeting a group of people and arranged to go to a movie with them the next day. But as she explained, “that apartment was pretty impressive, and I thought I might as well show it off”, so she invited them all to meet there first, for a drink. When she opened the door to them, they had brought a man with them who had not been there the night before. He was standing at the back of the group and she could see only part of his face and head. But just seeing this fragment of him was instantly and overwhelmingly exciting, and yes, this was her husband-to-be. What could have transmitted this powerful effect, it was enough to make one believe in ‘auras’ or ‘astral rays’, or simply fate, something quite different from needing or desiring to have free introductions to housewives for a trial period, though even there, life changing meetings must take place.

Verbal language thought w-e can relate to experience as an extrapolation or distillation, that gives an expression of a state, is a result of something, but in itself it does not account for the hormonal flows, the ‘astral rays’ or ‘fate’. “I love you” is the outcome of complex processes and these processes must also ‘speak’ or the words will be empty.

Most of human life goes on invisibly inside the body, breath, blood flows, digestion, the deepest most intimate functioning is beyond our experiential tracking, we can understand intellectually how the breath and blood are inter-related, but that is not at all the same as experiencing these processes. She knew that the language of explanations resulting from experiment and investigation also becomes void when separated from the experience of discovery.

This is how the noble truths of scriptures had become theoretical constructs, dams which hold back flowing experience. Small verbal expressions of something once experienced are held fast to as the ‘truth’ itself, and from this rules and modes of behaviour and belief, notions of immutable laws are formed. Emotional understandings reached through grief, fear or love find verbal forms but these become obstructive matter, gathering into rotting sores of resentment, jealousy or rage clogging and congealing, preventing the proper exchange of substances.

In both these cases life is restricted, the body of language becomes dust or slime. w-e realised that this is why she must abandon whatever she regarded as ‘wisdom’ start again to let life wave over her, she must allow for and value confusion, the hormones, all the invisible processes, the ‘rays’, and ‘fate’ itself. Though some things have to be held onto, some knowledge, some modes of doing things, ways to function retained, everything can not be let go. But knowledge itself is not wisdom, and it is the reverence for, or the privileging of some special knowledge, that becomes dead wisdom and must be let go.

The sound of cotton

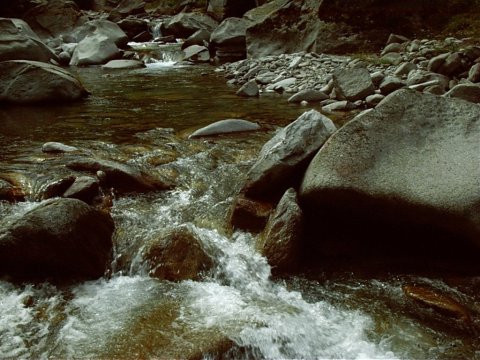

Once these fleeting thoughts about language began to flicker, they connected unexpectedly with experience. As she put on her long white cotton nightdress she felt the pleasure in the sound the fabric made, the wrinkling and straightening movement of its substance was like the gentle breaking of water over rocks in a small stream, something that she loved to listen to.

When she was in Italy the family she stayed with used to go out in a large group to walk in the mountains, when they learned of her liking for the sound of water, they all stopped talking as they crossed small rivers or streams and stood still so that she could hear it. Were there a new cousin, or friend in the party, they would hush them, saying “she likes to listen”. Seen in the Italian context, the cotton sound could be thought of as a bit of a, by association, an indirect ‘madelaine’ moment. But in itself the sound spoke of something soothing, as did her computer which gave out a stream of sound as its innards whined, fluttered, gurgled, hummed, gave notice of its processes, signalling activities, the stalling and restarting of them, all these kept her in tune with the machine. She had speakers, but had disconnected them disliking the programmed noises that came through them.

Before she fell asleep, the images of the mountains came back to her, and the husbands on the family group walks who used to pick flowers and give them to her so that she ended each walk carrying a bridesmaid’s bouquet of wild flowers, and her fear that the wives would hate her, but they hadn’t, the wives had been tolerant. Italy and Italians had rinsed away matter surrounding the certainties of Protestant morality till these notions emerged for what they were, a way of being, a set of rules, or as Alice would have said ‘nothing but a pack of cards’. Not that they themselves were not imprisoned in their own delusions, so rigid in their own assumptions that w-e could not even talk to them about some subjects, there being no common ground at all. Their freedom lay in holding sets of what she would previously have thought of as conflicting emotions, they were not troubled by this, did not spend time as she did striving to find out which was the ‘right’ emotion, or the ‘real’, or ‘true’ emotion, they lived in a multiplicity of feelings which they accepted, as they accepted her, relating to her in a network of emotional modes none of which threatened exclusion. When she felt that she could not impose on this family longer and ought to move out, they had been horrified, called a family council round the dining table and said she wants to leave, she is unhappy, “Why?”

When she explained that at home people did not go and live in other people’s houses for extended stays, they just said “we do here, we’re used to it, you are no trouble to anyone, you dress yourself, you feed yourself, you have a nice room, you eat well, in Italy if you have all that and leave it, we call it stupid”. It had taken some time to convince her, one day the husband managed it. “Look” he said “let’s settle this once and for all, this is your home, you can stay here for ever, until we are all white-haired and walking round on sticks”.

Memorial

The day after these explorations, w-e set out for a pub to meet some people before going on with them to a church for a memorial service. When she found it the pub had a series of tiny rooms, corridors, little alcoves, it was crowded and dark, she toured around it anxiously a couple of times unable to find anyone she knew, and then sat outside in the bright freezing air at a table where she would be visible. But the time came to leave for the church and she went off on her own, finding the huge church, part of a monastery lodged on the edge of a hill, closed and with no sign of anyone else waiting. She walked back to the house of the friends she was due to meet and there was no one in.

So back up and down and up the hill she went again to the church and this time the door was open and she entered. She saw a photograph of the young woman who had died propped on the alter steps. In the black and white picture, her eye sockets were completely in shadow so neither open nor closed, giving a disturbing skull-like image as though she were half way between life and death. In front of the photo were a pair of red shoes, a book and a candle. Behind this arrangement the church soared up to a dome over a massive Romanesque tomb-like high altar set in pillars and overhung with stone angels, poinsettias blazed in the distant recessed ledges of it. The church walls had been painted in a number of colours that w-e recognised as being from the tasteful National Trust paint colour chart.

There were a few people there all young and looking responsible, moving things from here to there and from there back to here again. There was an older woman in a black fur who, when w-e asked her if she was the mother of Adele, said she was “the mother of the best friend”, that there was not going to be a priest, but people were going to share their memories. “When you see a voluminous woman”, she said, “that will be her mother”. w-e was uncertain where to sit, it could not be like a wedding with friends of the bride on one side, and of the groom on the other, she sat on the other side from the fur coated woman, and a German young woman, who was organising the music, remembered meeting w-e and came up to her to ask if she was alright, which she was, having only really met the Adele once at her birthday party two years before, she had spent a long summer afternoon wrapping up a bottle and drawing on it, picking flowers from her balcony, collecting things to take her. It had been a happy evening, Adele glamorous in a fifties’ frock. w-e felt as though she had no right to be at this memorial sharing, yet she had been shocked by the sudden unexpected death of someone so young, she had wanted to come, imagining that there would be a mass with hymn-singing and prayers.

The music organiser knelt down by the pew w-e was in, she herself was not at all alright, she said she was playing songs that people had asked for because of memories, and strains of Leonard Cohen’s Suzanne wafted miserably from the machine at the side of the church. The door right at the back opened from time to time and people came in, then after some while the door opened and a whole crowd of people who had been to the cemetery to see where the ashes had been interred, came in all together, a large black clad sober crowd, w-e’s friend Nicola among them and her flatmate, they brought in icy air which fell about her feet.

The ‘voluminous’ mother sat in front of w-e and Nicola, she had a bundle of papers and wrote with fast jerky writing, until someone stood on the steps and began the process of sharing their memories of Adele. Then she ran her right hand through her hair, pulling and patting it’s short reddish strands and began to emanate powerful waves of feeling, her body opening up with laughter at some stories and at other moments collapsing over with shudders of silent crying. w-e was so near her that she could not avoid the pain and her own body began to hurt, she leaned forward instinctively, feet on the kneeler, her chest closing up to her knees, she noticed that Nicola and her flatmate had adopted exactly the same posture. The temperature in the church dropped steadily, Nicola warmed her hands in her hat using it as a muff, w-e wrapped her feet in a wool shawl and thanked god that she had put on as many layers of t-shirt and jumper as she had.

Then Adele’s mother got up and went to sit on the alter steps, taking her bundles of paper with her, she said that she was used to speaking, and wanted to speak now, and she did. Her voice was strong, she talked of Adele, of her family, Adele’s birth father, their Latin origins, their culture, her own spiritual beliefs, the significance of the date Adele had died on, which was Epiphany, of the cemetery being on the flight path for airplanes, and having also the natural flight of the birds, and now too the spirit, layers of aerial significance, her memories of having sat there in the grass with her daughter; Adele as a child, tap dancing on a table outside in the porch, at a wedding which they did not have because the video had run out. She talked of the people who had cared for Adele while she had had to work, her friend who had been Adele’s ‘other Mom’. She recounted the phone call in the early hours of the morning coming across the continent from a tired doctor at the end of a twelve hour shift, to tell her the news and how she said in her terror “bottom line, bottom line, bottom line,” needing to hear the worst actually said, “and then the doctor said, you know, Adele is no more.”

She said how much it meant to her to meet Adele’s friends, to hear their stories, because since Adele had left home they had seen so little of her. The cold clawed and w-e’s sitting on bones bored into the pew. Adele’s mother talked of her own processes, her narrative was full of turns and time-twists, reflective, insightful, questing, looking into her own future, like an underwater plant, opening and closing in response to the swirls of water surrounding it, she had many things to say, and she went on saying them. She read an essay Adele wrote when she was sixteen after the death of her father, she read Adel’s commencement speech which ended “What are you going to do with your short magical life?” The mother asked this question “ of all of you here now”, she had finished. W-e and Nicola put on their hats and stood up, but the mother ran forward, there was something important that she had forgotten, she was crying, w-e and Nicola sat down again.

Then it was over, and there were groups of people, standing not quite leaving in the dark church, and the music played was Son of a Preacher Man, an oddly heartrending song, playing into the ears of this group of people from a time long before Adele or any of them were born, and w-e and Nicola eased themselves from the church and walked briskly to the flat people were coming on to for a drink.

Nicola hurled olives and salty biscuits into bowls, got out glasses and bottles and put the kettle on, they had just made themselves warming mugs of tea and coffee when the first people began to arrive and stand round edgily. w-e talked to a couple of people and then found herself in a doorway obstructing the general flow with Adel’s mother, who came up the stairs in a wet coat and would not take it off, though w-e tried to relieve her of it, but she didn’t want it to be taken, “For now” she said “I want to stay here and talk”. w-e thanked her for all she had said and added that British people were not good at all at sharing stories about their friends, and how she had been at the private view of a large memorial exhibition for a painter who had died in his eighties, much loved by generations of students, and not one person mentioned him at all, they held their glasses and talked of other things, and at the time she had been shocked by the whole emotional atmosphere of denial, the loss of opportunity.

The mother hugged her and said, “I know almost everyone here, I saw you at the church and I felt you were encouraging me, who are you?” w-e gave her the mug of tea to hold to warm her hands up and explained that she was no one in particular, had been to Adele’s birthday party and wanted to come. She wasn’t able to say that what had hooked into her heart had been that she had wished Adele many happy returns, and there had in fact been only one birthday more to come. Somehow they talked about the process of dieing, the experience of witnessing the spirit leaving the body, and all this intense talking was being done with people pushing back and forth through the doorway. w-e tried to nudge the mother into a more comfortable place, but she was immovable, the mother’s friend, Adele’s ‘other Mom’ was standing the other side of the doorway w-e reached out he arm to try to bring her in with them, but it was not possible, so she stayed where they were on the landing and w-e left only when a Portuguese young woman came to say her goodbyes.

She went briefly into the main room now full of people, the photo from the church was propped up by the mantelpiece it had temporarily lost its icon status and become a thing among other things to be picked up, carried about, put down. There was a lap-top with pictures of Adele on it, one of her friends was trying to find out how to operate it, w-e went out onto the landing and leant in the doorway into Nicola’s bedroom, the ‘other Mom’ was also there and, though she refused a seat at first, did sit down.

It must have been hard for her, she had looked after Adele a lot when she was a child, she too must have been suffering, but the role she had taken for now was to support Cristina-Maria, “I don’t think its sunk in yet” she said, as they looked out of the door through they could hear the strong the voice of her friend, “what happens when there is nothing left to organise, to arrange, to do?” Deaths and experience of deaths rolled out of their memories, from and into a kind of universal stream.

On her way home, w-e remembered a talk by an academic theologian about the ear as a female organ in contrast to the eye which is male.

The theologian, a woman, had said that the ear receives, but the eye penetrates, and that in theology the organ overwhelmingly referred to is the eye, and the activity sight, that we see into, looking into things. But this was probably, thought w-e, because the theologians had been male, after all the eye can receive. Her thoughts wandered, Inanna’s journey had started from listening, setting her ear to the ground, pulling her awareness into the dark, where eyes would not serve her. But then again, Ereshkegal could see, had a terribly eye of death which she set upon Innana.

The listening that evening had been a rare communal activity for w-e. She thought of god, in the words of the hymn, ‘immortal invisible, god only wise’ she could not remember god described as inaudible. Her journey home was slowed down by train changes, longish waits. Next day she looked up eye and ear in her Biblical concordance and found 78 lines of references to eye, none to eyes, and only twenty-four to ear, and two to ears. She wondered if the Biblical use of the singular, where we usually use the plural, had resulted from translation, from some usage in Greek or Hebrew.

Checking out at the supermarket

A couple of days later w-e found herself at the checkout queuing at the till of a kindly woman she had exchanged some words with during Ramadan, when the woman was tired due to fasting. Back then, while they were packing w-e had asked if she knew that Christians also used to fast, though not exactly in the same way, but that they had Lent which was a period of fasting, not held to with any strictness now by most people. “But why not? It is good”, said Schara, “you appreciate so much after fasting”. Now, while she waited for her turn at the till, she heard and then saw a grappling hand that tried to extract the plastic purchase divider from its slot, w-e gave it to the woman who had the round eyes of the very old, set like wrapped berries in a strong happy face, once w-e’s shopping was underway and moving through, this woman came round to the exit side of the till while her friend placed their shopping on the counter. She had a stout wooden stick and showed no sign of wanting to sit down.

“My hands are so cold” she explained, “it is freezing outside” said w-e, “I’m ninety-one, my hands are old, and I’ve just got over the ‘flu’ said the woman, explaining her difficulty with the purchase divider, w-e admired her for overcoming the ‘flu’ still recent enough for a mention of it to cause a sympathetic ripple of reminiscence round the till. “But I still don’t feel like a round of golf” said the woman.

Jealousy

Overcome by the emotions of the memorial event and her confused thinking about organ theology, w-e now felt the need for a specific focus elsewhere and embarked upon a new Google search. There were two million, two hundred and ninety thousand hits for jealousy, the first few about the control, overcoming, or handling of jealousy, ‘Managing Jealousy in Open Relationships’ looked like a site that might be much referred to, if people in open relationships had time for sitting in front of a computer’ thought w-e somewhat bitterly, perhaps jealously. She was drawn to the site which flagged “don’t deny jealousy”, but it turned out to be a site about polyamory, both ‘partners’ in a marriage having multiple other partners, presumably sexual, and how to handle the whole thing with consideration for everyone involved, how to politely avoid unpleasantness in gatherings where several of each partners other partners might be present.

“There is so much to be grateful for” thought w-e, complacent in her lack of a partner with multiple other partners and the merciful lack of opportunities that this would have afforded her for learning the appropriate managing strategies.

At http://www.planetwaves.net/jealousy.html she found ‘Jealousy and the Abyss’

by William Pennell Rock, from the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 2, Spring 1983, 70-84 ©1983 by the Association for Humanistic Psychology.

His abstract read: ‘Relationships – and jealousy in particular – provide an opportunity to come to a fundamental understanding of the self. Jealousy is the eruption of attachment. It can be transcended only through awareness. As we move with awareness into the core of this phenomenon, we pass through ungrounded expectations and beliefs, projections and delusions, envy, guilt, the loss of self-esteem, and the threat to security. The core is an existential problem; it has to do with illusion and the essentially fearful nature of the ego. In possessiveness, ego defends itself against nothingness. When we come to know and accept the nothingness at the core, jealousy and the pain of obsessive attachment cease.’

This Olympian view of jealousy while interesting to the impartial and uninvolved reader did not seem to w-e to be something that would adequately deal with the jealous wrath of a goddess. Ereshkegal was suffering the death of her husband and had been buried since the beginning of time in the dark earth whilst Innana reigned above on the sunlit earth with her husband and children, adorned and loved, probably her jealousy could not be experienced, looked at or treated separately from her killing rage.

The website on which this appeared also had the picture of a mid-thirtyish middle-Eastern looking man with a long bony face, who was reaching for cuteness by way of a knitted hat pulled on ineptly and crookedly as though by a seven-year-old, his coat collar up, his lapel decorated with a child’s plastic badge, his head on one side, his smiling lips looked as though they must have been enhanced by many dollars worth of enlargement injections. w-e felt irritated at first, and thought that he was in the process of distorting himself, but then she realized that he might in fact be trying to show outwardly the part of himself that had never received any attention, but that unfortunately he would probably attract bullying adult-children as much as a kindly parent adult-children to play out his drama.

Donne’s poem

Donne’s Elegy 1: Jealousy which she also found on her search, danced round the difficulties adulterers’ experience, praising the jealous husband for letting them know he is suspicious, suggesting they take themselves somewhere other than his house or bed to play. But this, on the face of it rather dull advice, sings to the sound of Donne’s music, is the poetic equivalent of the hand that finds the zip, that strokes and carries on, defeating protest.

Though not admirable by some moral standards this advice was a joy to listen to, more of it might have been included in Advice, most of the material for which had now been submitted to the publisher, but the book itself had had its publication date put back. w-e was partly bored by the torrent of advice with which she had been dealing, but was also more and more sure that advice worsens most situations. Take the advice of the jealousy man Rock, to realize the nothingness of the core, supposing you could, or thought you could and somehow deceived yourself, got it not quite right, what then? Besides, nothingness is surely difficult to recognise, one would be forever saying “is this nothingness?”. And if there were a this, surely it would not be nothing?

She remembered the great storm of the eighties, the public response to the loss of trees, the funds raised for buying new trees, the urgency and commitment to re-planting. Yet a decade later, studies showed that natural reforestation had overtaken human attempts to restore the damage. Left alone nature had done it better, had they known it, the best advice would have been to leave things be, and yet of course this could not always be the case. The catastrophic great wave could not be responded to like that, people could not be left to starve and die, in the knowledge that those remaining would repopulate and replace the dead in a decade or two.

Just the same, w-e had begun to think that direct action, the ‘taking charge of your life’ approach of so many self-help books, did impede natural integration, they focused on the ‘problem’ so fiercely that trust in life itself was atrophied. on the other hand, though despised by the rational, open the heart and mind to completely new experience, free the imprisoned mind from the limitation of certainties, contradict the accepted wisdom of the time. It is acknowledgment of the possibility of, or the embrace of miracles that allows them to occur, and more importantly than creating trust in god, they create a trust in the flow of life itself.

Helmshore refurbishment

The housing association had recently shut down and sold off many of its properties, and there had been unsettling rumours about the future of Helmshore itself. But now, as Sylvia had told w-e some days before, the housing association had received European government grants of nineteen million pounds for the refurbishment of their properties and because Helmshore had never undergone anything in the way of improvements since it had been built, this is where the necessary works would begin. There would be a meeting in the common room that evening to go into it all.

Butlers in tailcoats with silver trays would be installed at the end of every corridor, ready to give kindly assistance to any elderly person who might require it. Taps with hot cocoa and cold champagne would be plumbed at intervals throughout the building for the encouragement of the mobile, w-e’s own idle fantasy seemed to have been called up by a recent re-reading of The Young Visitors, and other excited imaginings came out during the meeting. These were to do with connections between the apartments, hatches through which food could be passed from one apartment to another, and tunnels through which residents in small bungalows could connect with the main building. The oncoming disruption had brought the residents out in a rash of Freudianly expressed anxiety narratives of regression, she wondered what other dreams the refurbishment might stir.

During the meeting there had been more giggling and hands coyly held over mouths than w-e could remember having seen before. While dreading the noise, chaos and brick dust to come the residents embraced the idea of change, and to suggest in a limited way that this was a regression gave no idea of their child-like enjoyment. It seemed to w-e that the Freudian terminology, which had in its time been a miraculously new language, one that had created a seemingly unlimited re-ordering of the understanding, had now shrunk to contain a limited set of popular understandings.

Although, once Freudian imagery came to mind, it was impossible not to see the new cordless, digital, hands-free speaker-phone telephone that she had just bought without some tinge of Freudian terminology, and also thought w-e excitedly with traces of organ-gender theology, which was, she could now see, an offshoot or byway of Freudian analysis. The new telephone was a phallus shaped object which slotted upright into the plastic hole of its separate base. Voices would issue from the tiny apertures in its erect head, its ‘face’ lit up and gave visual messages, mysterious clues as to its state of functioning which she had not yet learned to decipher. The old telephone handset lay passively, attached by an umbilical cord to its mother, it was ear orientated, had no visual messaging at all.

The Inanna story itself was susceptible to Freudian analysis, but this did not spark anything insightful, apart from the sex-death association, in which Inanna became an unlikely lock-knit clad Woody Allen kind of sperm penetrating the body of the earth and meeting her end in the throne room of Ereshkegal, where the eye of her sister fell upon her and she became a corpse, a piece of rotting meat, hung on a hook in the wall to decompose in the womb of the earth, a kind of inversion of human conception and gestation.

Rotting

Christ’s decent to harrow hell, to quicken the souls of the dead came from the same family of descent stories as did Inanna, Persephone, Hercules, and Orpheus, though the hero stories seemed more Freudianly precise, representing a male act of creation, the spirit penetrating matter and bringing life to the dead.

She knew that the whole question of rotting was a worry for theologians. By the time Christ reached them would Adam and Eve would have rotted unrecognisably, mingled with the earth so much that their bodies could not be resurrected? Also at what age would the body be resurrected? Would this be the age the person was when they died or sometime earlier, would a body that had lost a limb be resurrected with it or without it? It would have made for a less conflicted dogma if earlier Christians had allowed the body to rot and the spirit to ascend to God. But as it turned out they had seemed determined that Christ’s dual nature, both human and divine. should manifest corporally as far as death was concerned.

The dual nature was hinted at in Jerusalem, there she had descended the first flight of steps into the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to see a screen of large jewelled eggs, hanging suspended in front of her. To her right the stairs had twisted down into the incense billowing air, a Disney stairway, lit by huge ornate pierced-work lamps and candles, she passed glittering grottos of significance to a variety of Christian churches Greek and Russian Orthodox, Roman Catholic, there did not seem to be anything Protestant along the way. At the very end there seemed to be a little hut, the size of a suburban potting shed. It was the tomb of Christ and had to be entered by bending down through a low opening. Inside there was a bed shaped bed sized tomb and on the dusty rock walls were hung small jam-jars, attached in a clumsy way by wires and holding offerings of wilting flowers. At the end of all the grandeur and ceremony, the official voices of the church were theatrically silent.

The computer brought her references to the lyrics of Rotting Christ, yet another sex ‘n death rock group. The cover of one of their albums did show the image of an exhumed and rotting Christ, which w-e deleted immediately she glimpsed it. It was not an image she wanted to examine, bringing as it did the memories of her own brother’s burial and the months afterwards in the distressing knowledge that this rotting process would be going on. In contrast, the body of her father had lain for months in a deep freeze while the slow processes for carrying out an autopsy gathered strength. This also had been unpleasant.

Not as horrifying as the exhumation of her friend Michel’s father’s body in its rotting state with one intact, perfect leg and shoe. For reasons she had never understood this had been legally necessary and Michel, his sister and mother had had to witness it.

As for Ereshkegal, with her eye of death, w-e realized that Ereshkegal was a personification of death, and, like the Death, who had advised her at the beginning of all this, not all powerful. Look at it in this way, if Ereshkegal ruled the kingdom of the dead why was she separated from her husband when he died? Was this because his body rotted and she was unable to stop or reverse the process? What kind of body did Ereshkegal have? There were anomalies in the story, things that didn’t fit, or background information that she did not have, this critical intrusion in her experience of the story surprised w-e, but then she thought, “the inevitability of death is not comfortable, it is not a story that can be told by the living, so I would have to find fault with it”, as her dream grandmother had advised she should not “make a friend of death.”

Death could only be made friends with in symbolically distancing terms, as in alchemy where the processes of rotting, or blackening were now seen psychologically as part of a voluntary descent into the inner self, a psychological death to the material world, or as w-e was herself doing, a scattering of her wisdoms, a sinking down into the inexplicable diffusion of the definitions of her randomly found words, an abandonment of their attendant certainties. This process had led her ruthlessly to the grieving raging Ereshkegal in whose petrifying presence she had no prescription, no explanation, no wisdom and no life. In this way she had understood the story in terms of her own experience and then understood her experience in terms of the story, and here this part of both her own and Inanna’s stories came to an end.

And now w-e was left incoherent, hanging on the hook of the story dead and gone, what did it matter if her imagined wisdoms were scattered or not, what did it matter? The restrictions of them, their binding had been unwrapped and no one can live without modes of being, patterns, illusions, lies, the lily pads across the pool, the way of smoke and mirrors. The truth was that it was not the giving up of her powers, her adornments that enabled Inanna to descend to Ereshkegal. Gate by gate death itself takes all powers and adornments, so any preoccupation with keeping them is vain, and in vain.

In the early morning she could not work, the computer screen reflected a dazzling light from the new energy saving light bulb. These bulbs, somewhat strangely, supplied free to the blind, and given to her by a blind person who not un-naturally had no use for them, were larger than the usual ones, they protruded down below the lampshades and this caused the difficulties. When she switched her overhead light off it was too dark to see and when she switched it on it was blinding and hurt her eyes. This had been the case for over a month, but now she could not tolerate the discomfort of it any more, was angry with herself for not having taken steps to solve this earlier. After an irritating amount of time was lost fiddling about with a reading lamp which needed a new bulb and had a dodgy switch, she decided to diffuse the light by extending the shade. She taped a white napkin to the top of it, but it fell off after a minute or two, her second attempt ended with the sticky tape falling on a book, where w-e had to leave it, as pulling it off would have obscured the text. After her third attempt with the tape she felt like an infant unable to disentangle herself, also she felt too hot in her jacket but too cold without it, she began to complain out loud, and then to throw things. She dragged a chair about to stand on to deal with the lampshade, and pulled a neck muscle. There was nothing for it but to switch on the television and watch the Bishop of Oxford, who was confusingly in Cambridge, handsomely smiling and nimbly hornpiping his way through a tricky interview.

Later, when this had calmed her down, she saw what she had begun to suspect earlier in all this, that Inanna had been lonely, and so had Ereshkegal, their ruling powers had isolated them from others, and from each other, who they were and what they were was wraiths, shadows, spiders whose threads had been pulled out to the very end. There was nowhere to be attached to, and nothing to attach with, their beautiful patterns were gone, there was no web for people to wonder at, no flies were caught, they were hungry.

Terminator Two

w-e now remembered the curious metallic entity in Terminator Two, a sci-fi shape shifter, silvery and metallic who flowed into a multitude of changing forms, she connected him with the handsome helpful Death who had morphed so suddenly from the Bacchus figure and realised that Death was Mercury, and that it was Mercury who flowed into the residents of Helmshore, her dream grandmother, the men at Homebase, the inhabitants of the graves in the cemetery and their imagined flower-bearing relatives, into Inanna, Ereshkegal and into everyone else in her internal and external stories, so all the time that she had felt on her own, she had in fact been accompanied and helped in the way she had wished.

This connective fluidity suggested that she herself must now allow herself to be taken, to flow into the being of Inanna’s servant Ninshubur, then into Enki, Inanna’s magician god of wisdom grandfather that the servant had gone to pleading for Inanna’s life, and then into the slavific flies that he made from the dirt under his fingernails.

The flies

The magical flies began to change the direction of the story. w-e recognised them as the helpers demanded in myth, who had to be there at the birth of a god, she had forgotten who it was whose divine child could not be born, who shrieked in prolonged labour because no midwife was present.

The flies mourn, they moan and cry, echoing every word of Ereshkegal conforming oddly to contemporary therapeutic practice. Their language is one of intonation, a transmission of emotion, of presence, the echoing language mothers speak to babies long before ‘rules for forming intelligible communications’ have been formed, a comforting cycle of repetition in which mother echoes baby and baby echoes mother. Each echo subtly changing, as the slightly shifting lines do in the story of Inanna, ‘she opened her ear to the great below, the goddess opened her ear to the great below, Inanna opened her ear to the great below’, each repetition bring the listener closer, moving them from the abstract ‘she’ through the formal ‘goddess’ to the name, to the one, to the one and only ‘Inanna’.

The calm steady buzzing of flies echoes the shushing sounds mothers make to calm their children, the agitated bombarding changes of pitch as flies career unsteadily round a space, getting near and then further away, these suggest cries of distress, and then, thought w-e, flies were always connected with death, with rotting meat, corpses. Flies laid their bundles of shockingly tidy white eggs on rotting meat, thus they were also agents of resurrection, and a subversion of the great divine creator above and of other winged beings, birds, angels, cherubim and seraphim.

Life-stories

w-e remembered Bishop Tutu, the reconciliation process in Africa where victims were listened to, their sufferings witnessed, their stories heard; the hours in which she had herself listened to others outflowing their pains, like milk expressed from overfull breasts; the stories told at Adele’s memorial event and afterwards when she, Nicole and Adele’s other Mom had sat together. Listening to echoes, taking soundings, these established place, and with this a recognition of limitation, if the listener attended closely they would hear the sound waves fade and eventually die out. But, surely she thought there could not be time enough to re-tell everything that needed to be retold, to listen to everything that must be heard, there had to be a moratorium, a grace of forgiveness.

She wanted to stop painful narratives leaking from the past into the present. She had to a certain extent listened to her own internal wailing, helped or hindered by ten different professional therapists and a multitude of amateurs kindly adopting the role temporarily. Each telling of the narratives shifted them, and this was the value of the oral tradition in which change was part of the process and each change in the story changed the past, made possible a change in the present and the future. Now to her distress the wailing that she heard was not on account of her own suffering, but of the suffering she perceived she had unknowingly inflicted on others. These memories rose from her intestines and hit her bodily, fountaining up, not as epic narratives, but as isolated moments, fragments of neglected perceptions that would not be contained. Perhaps the listening and therapeutic echoing had to be integrated, a constant part of life, not split off into performances, or rituals carried out only during the therapeutic hour, in therapy rooms, but running on like the water over stones in the Italian hills.

Love and the most noble truth

The noblest of all truths is the life-story spun from experience, and patterned by the noble truths received from others, the family, the culture, the archived accounts of events which were even now decaying in whatever form they had been captured. The curating of noble truths was taking more and more of her energy. The most important stories must be lost through retelling. She settled down now to tell the story that seemed to be the central hub from which life radiated. It was this.

She had been told that love was something she would experience later, in its deepest form from having a husband and her own children, though to judge from the husbands, mothers and children around her, this did not seem to be so. If she did not do this she would remain forever lonely and unfulfilled as a woman. At the same time, once she entered married life, she would cease to be an individual, would have no chance to explore or use her talents, she would remain perpetually frustrated and unfulfilled as a person. This inescapable twisted strip of life had held her in paths of endlessly looped misery.

This was, of course, she now realised, her mother’s life-story, refined of all impurities, retaining its contradictions, it had been her mother’s involuntary gift, probably in all kindness an attempt to warn her what life was like, and also as an ease to her own suffering, an invisible insurance against seeing her daughter live differently, because then she would have suffered even more, seeing that there could have been a resolution of a kind, that it could have turned from tragedy to comedy.

Her mother’s life story had also been inherited and so on back through time, these stories even if not actually told in words were still explicitly understood, valued because they came from the deepest longings, they are the un-echoed cries that remain internal. By passing on the same pattern of emotional need, her mother had made her an echo, a magical fly, a companion whose mirroring had eased her own suffering, her loneliness.

Lent

A couple of days into Lent, w-e found herself in a stinging drizzle turning into the drive of the cemetery, she saw the laurels splashed with vivid yellow shining through the brambles, the honeysuckle renewing itself, a small clump of budding daffodils by the entrance.

Once inside she could see that things were on the move, spring had not yet arrived, but changes had been made, although some of the Christmas poinsettias remained daffodils were coming up everywhere, some in recently planted patterns inside graves, some dotted irregularly, the incoherent remnants of past schemes, there were edgings of bright polyanthus primulas. A large triple grave with blue and white hyacinths in full flower blasted out its perfume, three empty urns at the head were labelled worryingly Mother, Father and Daddy. She wondered what narrative lay behind this triple burying, why the order had been as it was, the choice of words which linked mother and father while seeming to cast daddy as the outsider, it was odd.

Turning into a path she had not explored before w-e walked between rows of old and decaying graves, most without names, some sinking into the earth, some seeming to rise up, breaking headstones and crosses which had been stacked back into the grave areas in a kind of stone club sandwich. In the grey light on the grey stones the mosses and lichens glowed golden and acid green, the bare earth, where a grave had been dug over, was red, there were some snowdrops in flower, and one grave was taken over by a dark spiky lavender bush. Further along were small graves, with so many names of grandfathers, mothers, sons, daughters, wives and husbands, that it was difficult to disentangle who had been what to whom, who exactly was in there. She noticed that the inscriptions on headstones and round the side of the graves had commas, but these were not enough to clarify the lists, paragraphing might have done it.

Back on the main path, outside the fenced off military section, she saw a crop of mushrooms exactly the colour of the fallen oak leaves, in the newer graves there were fresh flowers, autumnal looking chrysanthemums, large expensive florist’s lilies. The sixties singer’s grave had a new black and white photograph of him tucked in among the flowers at the foot, only the quiff of hair showed above the stonework and flowers. At the back, at ground level was a new oval colour photo of him in a gilt frame smiling shyly up into the eyes of the passer by, baskets of cyclamen, hyacinths and miniature daffodils in bloom showed that he was still loved, remembered. The other side of the holly berried bush which bordered this shrine, there was a zen-like grave, a flat, smooth oblong of cement with a triad of oranges shining like suns with puckered green nipples. It was raining more heavily now, she rounded the curve of the path and saw the gave with the oil lamps, there was no one about so she walked over to see what was happening.

A muddy area around this grave showed that it had been visited a lot, and indeed there had been changes, additions. To say that a grave was infested with fairies sounds unkind, but this grave was overwhelmed by fairies, some were tiny, an inch or so in size, others larger, a leaden sleeping fairy with folded wings, two smaller green garden fairies played on a sea-saw, others knelt, beseeched, sat pertly on the edge of the grave with legs crossed, more appeared as she looked, and with them flights of cherubs in whose white chubby hands coloured glass prayer beads had been placed, there were angels of a more traditional kind, standing in guardian position or leaning on empty plaques, these spilled out onto the muddy area surrounding the grave, where there were also two statues of girls holding dogs, and a miniature wooden wishing well, planted with winter pansies. It was raining more strongly now, one of the lamps swung gently on its hook, the other nestled among the fairies, their lights looked dusty, dimmed by the translucent brilliance emanating from the grass and flowers around them.

First time reinstatement

On her way to the station w-e came across a young man walking up and down a section of the verge which had a raked earth surface. He had a small bag and was scattering seed from it in a way that made her think of medieval woodcuts, he seemed to be permitting himself a pleased smile. His large municipal van was nearby, it had the initials CBD and after them the odd phrase, ‘First time reinstatement to the utilities’, a baffling legend thought w-e, it was on both the side and the front of the van.

When the train arrived w-e got into a carriage with a sleeping man in it, she called softly hoping to stir him, but he slumbered on, sunk down and curled over, so though it was the end of the line and the train would take him back from where he had come she felt that sleep was what he wanted most, perhaps he had even got on the train as somewhere to sleep out of the icy drizzle. There was no way of knowing, seeing the sower had been a good sign, an omen, her mind wandered. She had begun to read Jung’s Answer to Job, had anyone written Job’s answer to Jung? Probably they had, she herself thought that Jung had missed the point, which was that there was no point to make, that finding an ideology in which suffering could be made somehow fruitful, was to be deluded. Job endured, he refused theories about why he was suffering, he continued to trust, to bear witness to life and in the end acknowledged that god was unknowable, and suffering a part of the unknowable, not a material, thought w-e, out of which ladders could be fashioned on which an elite might ascend to somewhere else. That somewhere else being a better place that the carpenters of the ladders, who could not make a whirlwind, had somehow brought into being. People were always doing something with suffering, she was herself, learning from it, struggling with it, or being in the process of overcoming it, conquering it in the way that in past centuries nature had been conquered, or else masochistically lying down in it, as though suffering itself had manners, or conscience and would take notice of how it was received or rejected. Noisy boys got on the train with their mobiles, they disturbed her thoughts, she moved to the next carriage. On the radio that morning a man had been talking about time and its flow, causality. He had said that when time was imagined to flow backwards a person would have a cup of tea and then after that put on the kettle to boil the water for it, that this was absurd. w-e thought not, she found it easy to imagine a world in which drinking tea would seem to give rise to the consequent boiling of water.

Once, on her way to the rose garden in Regents Park, she had suddenly experienced the universe as being one complete whole, in which one thing did not follow from another, but in which everything already was. This was not something she could bring back into any reasonable verbal formation, when she tried she babbled and conveyed nothing, so she gave up. She did know though, that she had received enlightenment, and as elevated as that sounded she knew also that she was just exactly as she had been before, apart, that is, from being enlightened.

Years later, after struggling once more to express what she had experienced a friend said to her ‘you saw the universe without time’ and that was it. What she had seen was that cause and effect were a delusion, time was a path taken through the universe, and that while it might not be possible to make time flow backwards, it was possible to be both within and without time, to oscillate between the temporal and the eternal.

___________________________________________________

CHAPTER: 8 RETURN – ENTOIL

___________________________________________________

Entoil, to entangle or ensnare

Entoil; sacrifice; day one – acquisitions diary Oxford Street; another day; hair; crossness and hairdressing; flowers, fish and disability beds; sunny day; veneers; conference entoilments; the Land of the Tulip; menu dream; replacement

w-e’s exploration of language had brought her to the completion of Inanna’s descent, her death and return to corporeal life, but the story does not end there with Inanna trapped underground, and w-e knew that her task now was to follow Inanna’s journeys, her ascents first to earth, then to the great above and lastly her return to earth as Goddess of all three realms. So once more she settled with the dictionary on her lap and randomly found the three new words she needed to help her follow Inanna’s path.

The dictionary had come up with entoil, another archaic word which her computer repeatedly restructured to read entail. In the context of Inanna the word made w-e think of the dark tangle of roots which held the goddess underground. When she looked up the word further she found that to tangle which was defined as ‘to unite confusedly’, came from the Danish tang or the Icelandic thange both meaning seaweed.

When the flies sprinkled life-giving water and life-giving food on Inanna she began to live and breathe but she was not yet free. She was entoiled, entangled in the underworld, in a passive relation to the word, she was not yet entoiling or entangling, but she would have to be, because there is no way to enter the world and remain separate from it. Eat or be eaten might be rephrased as entrap or be entrapped, ensnare or be ensnared, ancient concepts coming from hunting times, when there was no deep freeze compartment between killing and eating.

In order to have her life back Inanna must find someone to send down to Ereshhkigal to replace her, and the guards that go with her will not leave her until they have captured the person she chooses, the person she condemns to death. So they set off back into the light.

Sacrifice

Self-sacrifice is the virtue of the fawn-cardiganed ones dotted singly among the empty chairs in church, or sitting immobile on the alter itself offering their inner arms to the institutions of church and state for the opening of their veins, the drinking of their blood.

“I was one of these, anxious to please, allowing others to speak for me, but now I can be rid of them, of their committee representative, I can speak for myself, and act for myself.”

This is the internal voice w-e heard unexpectedly, she was startled by some ruthlessness in the tone, some readiness that she had not heard before to pursue her own life, she did not wish to sit and think, or to hide away safely, or to refrain, she wished to act.

Although shocking, this voice had not come out of nowhere. She had in fact acted to give up the interviewing she was doing for the publishers. It had been unsatisfactory for some time, but it had been a security of a sort. Now she realised that hanging on to the security was in itself a full time occupation and even at the risk of finding something worse she could ‘let go of nurse’. Being willing to abandon her wisdom was the same thing as being willing to abandon security, both were delusions.

Uncertain how to proceed w-e took temporary refuge in a Google search for ‘sacrifice’ it brought her two equally depressing hits, one for a vapid lyric to an Elton John song, and one to an encyclopaedic site which chronicled sacrifice through the ages, often the sacrifices were of children. The drama of sacrifice was an unpleasant one, it could not be escaped by changing roles, to swap being sacrificed for being the sacrificer, because whichever role was taken the story was equally horrible.

On the other hand, by adapting her established methodology, the story could be expanded rather than diluted, mixed in with other stories, more of a shifting spectrum than one specific colouring of life events, and although she was framing her own story within that of Inanna, this entoil part of the story was only that, a part, she did not have to stay in it, solve, or understand it, she just had to live it.

Thus the expansion that she needed now was not of a contemplative nature, but one that demanded excursions, carnival, participation in other people’s stories. She got her diary out and saw that she was due to have three meetings and a clothes buying outing, two of the meetings were tidying up things for the publisher, the third was with her accountant/bookkeeper to get her papers in order. The clothes were necessary for a conference she had organised that was happening the following week. Later no doubt there would be other occasions more pleasing, perhaps more adventurous, taking her into unfamiliar atmospheres, but she did not have to worry, because this pioneering drive inside her would propel her outwards into the stream and flow of life.